My sister sends me a text: “Here’s something for you to write about!”

This is a regular occurrence. It’s more regular than, for example, the sun rising, or setting, or the arrival of the post — that is to say, she does this several times a day, sometimes to my delight but often, I confess, to my frustration (and she knows this; it’s a show of true sisterly love that it doesn’t put her off).

Technology now allows that she sends these suggestions — suggestions that often feel like instructions, perhaps because of the tone but more likely because she is my older sister and every suggestion she makes feels like an urgent command, something I must carry out immediately, an impulse I try my hardest to resist — not just by text but also via Instagram, where I’m frequently sent links, accompanied by similar notions.

“Would you consider this?!?” accompanied a link to an interview with an OnlyFans creator who is speaking about her monthly income of $400,000. Would I consider starting an OnlyFans? my sister wants to know.

I would, honestly, because I love money and have no shame, but I’m also stubbornly resistant to the labour that goes into being glamorous, and I’m also still (and no, this didn’t disappear at 40, the magazines all lied) disturbingly concerned with what other people think of me.

I ask my husband what he thinks. “I would,” he says, carefully (very uncharacteristic, honestly), looking directly at me — which makes me think of just how often we speak to one another while looking elsewhere, at our children or, more often, at our phones — “do my best to encourage you not to start an OnlyFans.” The word he’s searching for is “discourage”, but I don’t tell him this. Maybe the idea of encouraging me not to do something sounds more positive to him.

“Why?” I ask, which feels like an important question to ask even though I know that he might be thinking the same things I’m thinking: it’s too exposing; where would I find the time; what would people think?!

“Well,” he says, again disturbingly carefully, “We have kids, for one thing.” I know what he means. We have kids, whose friends might cotton on to the fact that their mum or stepmum has an OnlyFans where she shares photographs of herself, or even — as suggested by my sister — videos of her lactating breasts.

(As I type this, now, I think, I’m not sure I could do this after all.)

Anyway, to park the OF discussion for the time being, the other significant order suggestion Beatrice sends me this week is that I write something about an Irish Times article titled, ‘We have enough Sad Irish Girl Wanders Around Dublin novels’. “Why just sad Irish girls?” she asks. “Isn’t that basically the plot of Ulysses?”

On the latter question, I’m not sure. I have an English degree — something I thought ruefully about today as I sprayed poo off the liner of a reusable nappy; was it for this, etc — but I somehow managed to avoid all 816 pages of James Joyce’s seminal work.

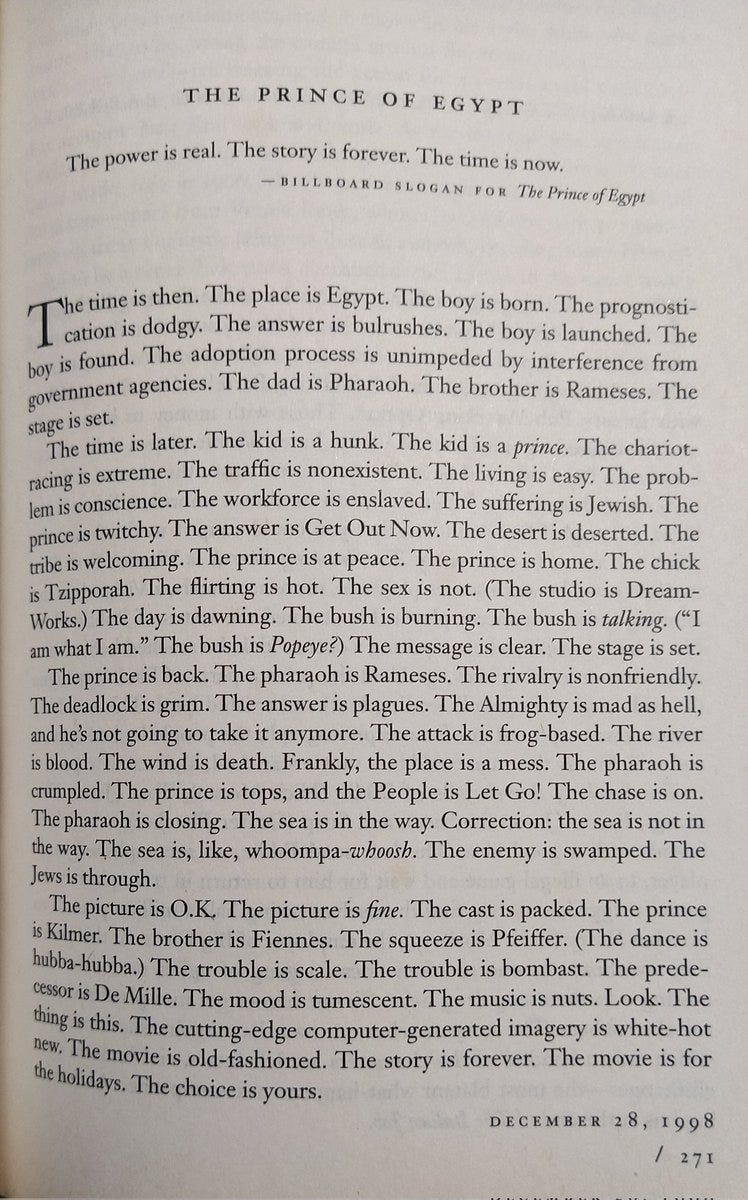

There was a seminar, I remember, offering Ulysses as a topic, but I chose to do another, on literary criticism, where we read Dale Peck’s Hatchet Jobs and William Zinsser’s’ On Writing Well and Anthony Lane’s Nobody’s Perfect, which is, even now, one of my favourite books. His review of The Prince of Egypt is something I like to read aloud to people. “I need to read you this hilarious review!” I’ll tell them. They never like it quite as much as I do.

I’ve thought, in the 20 or so years since I graduated (Christ!) that I should probably read Ulysses, especially as I now find myself living in the US, and being able to say I’ve read Ulysses feels like the kind of thing — one of many — that would distinguish me, an Irish person, from every other person in America who claims to be Irish, too.

Anyway, to Beatrice’s point: Ulysses, Google tells me, tells the story of a day in the life of three Dubliners, two of whom are indeed men, the other of whom, while being a woman, is identified by her relationship to one of the first two, who happens to be her husband. So, Bea’s point stands.

Still, I tell her, I can’t write about it. A few years ago, I shared on Twitter some criticism of an Irish Times op-ed I’d read, an essay which, without naming her, criticised the decision of an Irish influencer to undergo a breast augmentation and share her experience with the procedure. The piece was about the beauty standards hefted at women in the public eye, particularly on social media, but it was also about this woman, particularly, and it felt, to me, kind of mean-spirited, like a snarky sub-tweet, but published in the Paper of Record, specifically because it didn’t name her, when it was very clear to anyone with even a vague interest in the social media realm at the time who they were writing about. (It’s depressing that, years later, it would be a lot harder to pinpoint the person in question — it would probably be easier to identify who hadn’t undergone some tweakment or other.)

Anyway, I then received an email from a guy I had worked with at the Irish Times, some years previously, accusing me of taking aim at this young journalist because of my own feelings of bitterness at having been dropped by the paper.

“I don’t write about Irish Times writers any more,” I tell Beatrice this week. “I can’t — won’t people just think I’m being bitter?”

“As you always say to me,” she responds, “Can’t it be both? Can’t you be bitter that you don’t work there any more, but also right in your response to something they publish?”

I mull it over, roll the idea around in my mouth for a few days to see how it feels. Maybe I can be both bitter and have an opinion that is closer to right than it is wrong. (You can be the judge.)

I read the piece.

What strikes me instantly is the idea that there are “good” and “bad” books, at least by some arbitrary literary standard. Surely the “good” books are the books you enjoy, and the “bad” books are the books you don’t or, if we accept that there are books we will enjoy and books we don’t, without those we don’t being bad, exactly, perhaps we then reserve “bad” for the books that are written clunkily, in prose that takes you out of the story, with plot points and character developments that feel jarring and unrealistic.

What’s more, the writer of this particular op-ed sets out her stall in the second paragraph, listing “good” work by three specific authors: WB Yeats, Arthur Conrad, James Joyce. Later, she will write, fleetingly, about the most popular author of 2024, Sarah J Maas.

“I am confident that I do not need the filtering effect of time to tell you this: the world’s bestselling author in 2024, Sarah J Maas, a pioneer of “romantasy” genre fiction, will not be up there with our Dostoevskys and Austens in 20 years time, or now, or ever.”

The idea that fiction enjoyed by women — and Maas’ books, which fit into the world’s most popular genre right now, romantasy, are, indeed, largely enjoyed by women — is unworthy of inclusion among the “classics” is not an original one, by any stretch of the imagination. And while we do get a mention of a single female author whose work passes muster — Jane Austen, who died more than 200 years ago — she’s mentioned only (and this isn’t original either) to denigrate the work of another woman, one with whom she is not in competition, although I’d say there is a significant crossover between people who enjoy Jane Austen and people who enjoy Sarah J Maas (*raises hand*).

That fewer people are reading than ever before, a prime concern cited in the article, is noteworthy — and depressing (although I do wonder if those figures take into account the number of people who are listening to podcasts and audiobooks, or even reading Substacks, a lot of which are incredibly well written and valuable both in terms of expanding worldviews and improving literacy) — but the idea that there are too many books being written, not enough of them good, is laughable, in my opinion (and this is not, I swear, my bitterness talking).

Think, for a moment, about EL James’ Fifty Shades of Grey, a work of Twilight fan fiction that was self-published in 2011. By the exacting standards of this Irish Times writer, maybe this book “shouldn’t” have been published. This will not come as a shock to anyone who’s read it, but Fifty Shades is not, by most people’s standards, a “good” book.

It’s trite, predictable, badly written. The characters are ridiculous and barely fleshed out. Their motivations are impossible to understand. And yet, the trilogy has gone on to sell 150 million copies worldwide. It has made its author, Erika Mitchell (EL James is her pen name) a multi-millionaire. It has been enjoyed – truly, enjoyed – by millions of people, worldwide, myself included (sometimes I enjoy things I know to be bad, okay? Ask me some day about smoking).

Who’s to say that Fifty Shades is less “good”, less deserving of its publication, than any other book? (And honestly, nothing is more off-putting to me than being told I “should” read a book, unless that’s simply because, “it’s so entertaining” – perhaps why I avoided that Ulysses seminar.)

Published literature, really, is like any other commodity, in that its value is decided by the demand for it. No matter how few people are reading, book sales – unlike, say, magazine and newspaper sales – have been rising, and I would argue that while, yes, we should be encouraging more people to read, having a wider variety of titles and genres to choose from is surely going to take us closer to, rather than farther away from, that goal.

If you’d like to read more books by women – once I left college, I realised that I was probably at an 80:20 ratio of male to female authors, and vowed to change that – some of my favourites include (alphabetical order for fairness):

Brit Bennett

Ali Hazelwood (also duh)

Emily Henry (duh)

Barbara Kingsolver

yes, Sarah J Maas (although I preferred her Throne of Glass series to A Court of Thorns and Roses, which may be controversial)

Rebecca Roanhorse (her Sixth World series is brilliant)

CJ Tudor

Catherine Walsh

Meg Wolitzer

You can follow me on Goodreads to see what I’m reading and what I give it on the five-star scale (anything two stars and below I thought was rubbish; three stars and up are for books I enjoyed – there is no guarantee that they would pass muster as three-, four- or five-star books by the standards of a literary critic).

If you liked this, you might like…

Why Are We So Obsessed With Fairy Porn, Anyway?

I’ve just finished Sarah J Maas’ Crescent City series, the latest in my foray into romantasy, a genre that is, FYI, in 2024, the subgenre — a hybrid of romance and fantasy, often involving faeries, werewolves, witches and assorted magical creatures, and

What Are Books Even For?

I’ve been reading a lot lately. I was going to write, “I’ve been reading a lot lately about…” and lead into the real meat of this piece, but I have a word count to fill, so I may as well give you the full back story.

I absolutely did NOT suggest breasts, I suggested FEET. How dare you.

That prince of Egypt review is so good, thanks for the heads up on the book!