Early on Saturday morning, I drive over to my sister’s house to meet her and a friend for a trip to Markle, a town about 20 minutes south of Fort Wayne where, I’m told, there’s a large antiques “mall” worth checking out.

I hear this from a woman on Facebook Marketplace from whom I’m buying some vintage kids’ wallpaper, a Sandra Boynton zoo print with corresponding borders which – to the surprise of no one who’s ever read my money diaries – I absolutely do not need and am not even sure what to do with.

As it happens, though we arrange to meet in Markle on Saturday morning, and I then rope the two gals in to come along for the drive – and a vintage shopping trip – my wallpaper lady finds herself in Fort Wayne on Friday evening, where we meet to exchange goods: a big box of wallpaper in exchange for thirty of my American dollars. A bargain.

The plan has been made, though, so, wallpaper or no, we set out to Markle bright and early, and find ourselves browsing through an enormous warehouse of vintage ceramics, clothing, cutlery and curios.

If you’ve never been to an antiques mall, they’re set out in “booths”, each owned by a different collector, or consignor, I guess, because can you call yourself a collector if you collect only to resell? I would say not.

There are booths dedicated entirely to Hot Wheels toy cars; booths full of prohibition-era glassware; there are booths that seem only to contain wooden crates of varying dimensions, with the odd sackcloth thrown in for good measure. There is what we call a “witchy” booth, with monkeys’ paws and witch balls and taxidermied crocodiles’ heads (Atlas would love that, I think, but of course I don’t buy it) and a shrunken head made, the tag says, of “skin and hair”.

There are milkmaid-style dresses – very popular right now thanks to the trad wife movement, you know – and denim jackets and cookie jars and lamps and vases and so many dinner sets: dessert plates and dinner plates and side plates and cereal bowls, set out and displayed on beautiful mahogany dining tables, complete with matching upholstered high-backed chairs.

“God,” says my sister at one point as she wanders from one booth to the next, resisting the urge, I know, to buy up every hand-stitched quilt in the place (her personal Roman Empire), “we really don’t need to make any new stuff, do we?”

In that context – in the context of the dying planet and chemicals and climate change and the finite resources we pour into the creation of new things as if those resources are, in fact, infinite – wandering around these vintage emporiums is a sobering experience*.

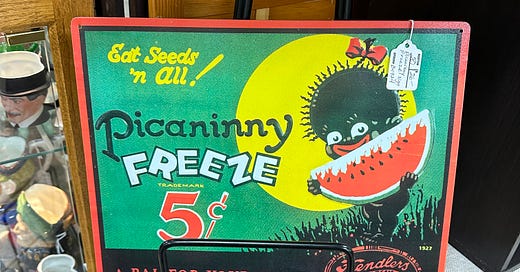

It’s sobering, too, for another reason; I have been to maybe a dozen antique shops, boutiques, emporiums, whatever you want to call them, in the Midwest – in Fort Wayne, on the road to Michigan, in towns around Indiana – and at each and every one I have seen many, many racist dolls, posters, sculptures and nick-nacks, and I’m not quite sure what to make of this.

I mean, for starters, I make of it: ugh. What a dark, disgusting and heartbreaking past the United States has. I wonder what it must be like, to wander around these malls, as a person of colour, to see how, exactly, your ancestors were depicted by the wealthy residents of a state that still has an active Klan membership. (I have never – not once – seen a Black person in any antiques mall that I’ve been in, which is perhaps unsurprising.)

It made me think of the recent fire that burned a former plantation in Louisiana to the ground, and the videos that were subsequently shared on social media, of a white tour guide showing people around the building, telling them just how happy its Black Slaves, who numbered around 155, were with their enslavement.

The destruction of the property – which functioned as a “resort” and wedding venue – prompted a deluge of commentary online about what can and should be done with these buildings, built by enslaved people at a time when a Black person could be bought and sold at market, raped or killed by their “owner” with zero repercussions, and whose children were born into that same enslavement, often separated from their parents at a young age to be sold to a different plantation owner, hundreds of miles away, with no more thought than would be given to buying or selling a horse.

I wonder if that’s a past people consider when planning their elaborate weddings on plantation property; did Blake Lively and Ryan Reynolds find themselves bogged down in “should we…” thinking as their wedding planner finalised the details of theirs, for example?

But while the Nottoway Plantation fire was celebrated – at least, as far as I saw – on social media by a lot of people who feel as though plantations shouldn’t be maintained as some sort of romanticised ode to a shameful era in American history, it’s not like we can burn them all to the ground. But should we?

Another Louisiana plantation, the Whitney Plantation, is a 200-acre former sugar plantation that now operates as a non-profit museum, offering visitors a tour of over a dozen historical structures, many of which are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Is there a difference, then, between visiting the Whitney Plantation and visiting somewhere like Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest of the German concentration camps, which operated between 1940 and 1945 and saw the extermination of more than 1.1 million men, women and children?

The problem, I think, with this comparison – and bear with me here – is almost totally aesthetic. To be clear, I haven’t toured either – though I was absolutely obsessed, in my teens, with Holocaust literature and documentary, and dreamed of visiting Auschwitz one day, I never got there, and don’t think I’d go now; and while we saw several tourable Plantations when we visited North Carolina last summer, the idea of paying to peek through the windows of an entire race’s past trauma seemed… distasteful, to say the least – but there is something about the stark horrors of Auschwitz that make it so clear that this is a Bad Place, while imagery of southern plantations is often so pristine and green that you almost need to remind yourself that all of this beauty has grown from the blood of Black people.

It seems to me that it would be entirely possible to walk around on a former plantation and forget its violent, reprehensible and heartbreaking history, something that, from what I’ve heard, is entirely impossible to do somewhere like Auschwitz.

Whatever about the plantations themselves — I’m not sure who among us would think we should raze those properties to the ground, even if, when one succumbs to an electrical fire, we’re not exactly getting out the hankies — the remnants of racism like those I see on Saturday morning in Markle are another thing entirely.

Do we really need to hold on to Picaninny Freeze posters, or find a place to display our racist dolls and ceramics? And is it morally right to benefit financially from the resale of these items, even now, 160 years after the abolition of slavery in 1865?

The items I saw, to be clear, are not the kind of Black dolls that were designed and created to give Black girls a toy they could see themselves in; no, these are golliwogs and Mammy characters, caricatures of Black maids and porters and cooks and chefs, clear representations of Black people in positions of servitude.

The thing is, try as we might to find a solution to the problems of the past, it seems like I’m entirely the wrong person to be asking. Maybe I need to look to Black people themselves to ask what they would like done with these items — things that represent the worst of our white privilege and a truly wretched time for our humanity — rather than walking around, tut-tutting under my breath in the very Caucasian antiques mall.

Kwame Anthony Appiah, writing in the New York Times, says that, “the destruction of historical artifacts is the wrong response to the moral horrors of the past” and posits that “most contemporary collectors of such items aren’t motivated by racism”, suggesting that any concerns about profiting from the sale of racist memorabilia could be assuaged by “sending the proceeds to the National Museum of African American History and Culture”.

David Pilgrim, too, the curator of the Jim Crow Museum, does not recommend the destruction of these objects; since he was a child, he’s been collecting racist curios, eventually donating his entire collection to the museum, the mission of which is to “use items of intolerance to teach tolerance”.

Of ridding himself of his collection, Pilgrim writes: “Most collectors are soothed by their collections; I hated mine and was relieved to get it out of my home. I donated my entire collection to the university, with the condition that the objects would be displayed and preserved.”

This LA Times feature suggests that these objects — Blackabilia, as they’re termed at one point — are often collected by Black people who wish to reclaim their heritage, or, as Patricia Turner, UC Davis associate professor, says, because there is such a dearth of Black representation in culture of the past, however not-so-distant. “I think about how excited my relatives would be when blacks first showed up on television,” Turner tells the LA Times, “and it really didn’t matter that it was ‘Amos and Andy,’ it was just confirmation that there were blacks in the world.”

“The only way that you beat these monsters is look them in the face and laugh at them,” says New York-based collector and writer Jeff Weinstein. “I hope that this can happen. But you shouldn’t be destroying these objects, so that the impulse that produced them will never happen again.”

It’s hard to look at them, these remnants of a way-too-recent history, that tell a story of a subordinated, abused and indentured people — but maybe I’m precisely the kind of person who should be looking at them. To remember, to reflect and never to revisit, even if sometimes it feels as though that possibility is closer to us than ever before.

*This morning, I started to think about buying waterproof hiking boots and lightweight waterproof pants, a uniform of sorts I could wear to the farm I’ve started working on (more on which anon), and decided to look on Poshmark, because surely there are a lot of those things I could find secondhand, from people like me who buy hiking boots for the one hike they’ll ever go on, and I discovered that one of my main problems is that I just have a distaste for the idea of wearing shoes that someone else has sweated into. Something I’m working on.

Weirdly, I’ve been to the Whitney Plantation and Auschwitz and the tours at both were excellent. The Whitney does a very good job of centring the focus on the enslaved people and the horrors they endured rather than on how “pretty” the buildings are, which seems to be the main reason why people get married there?!! Madness.

Unfortunately, there was an Irish American there the same day who insisted on saying “the Irish were slaves too!!” (mortifying) as the incredibly patient tour guide explained the difference between slavery and indentured servants